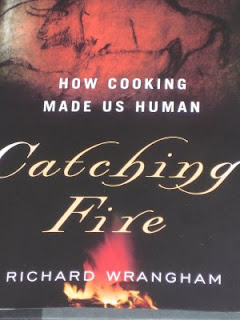

As an unabashed food history nerd I was excited to hear about this new book, which makes the argument that the domestication of fire was the impetus behind many important evolutionary developments.

We have evidence of the widespread use of fire by humans starting about half a million years ago, but Wrangham argues that it must have started much earlier than that, based on the fact that human stomachs and teeth began shrinking between a million and a half and two million years ago, evidence that human diets became softer and easier to digest.

I was fascinated by his discussion of how long our simian cousins spend chewing: some as much as six hours a day. This amount of processing is necessary in order to break down the tough, raw foods available in jungles and savannahs into useful nutrients. The act of cooking dramatically lessened the amount of time we had to spend chewing, freeing us up for all kinds of other activities, like music, hunting and philosophy.

I did have trouble with his discussion of cooking and gender roles. I've never heard a satisfactory explanation of the almost universal division of labor that delegates cooking to women and hunting to men: it seems nearly impossible to me to come up with a satisfactory hypothesis when we're filtering information through our own experience and social conventions. But Wrangham's theory seemed especially silly: he believes that women were particularly vulnerable while they were cooking, so they needed men to protect them. Hence the development of human pair bonding.

I think it's more likely that the men were being annoying and getting in the way, and the women sent them out to hunt, knowing the activity would get them out of the homestead for an extended period of time.

No comments:

Post a Comment